Content:

1.The Importance of Glass Packaging

1.1 Packaging Is the First Line of Protection for Glass

1.2 Packaging Directly Affects Breakage Rate and Supply Chain Costs

1.3 Packaging Compensates for the Inherent Weakness of Glass

1.4 Packaging Is the Only Controllable Factor in Complex Transport Environments

1.5 Packaging Reflects Supplier Professionalism and Influences Customer Trust

2.Common Materials Used in Glass Packaging

2.1 Protective Film

2.2 Paper-Based Packaging Materials

2.3 EPE Foam Bags

2.4 Plywood Carton

2.5 Honeycomb Paperboard

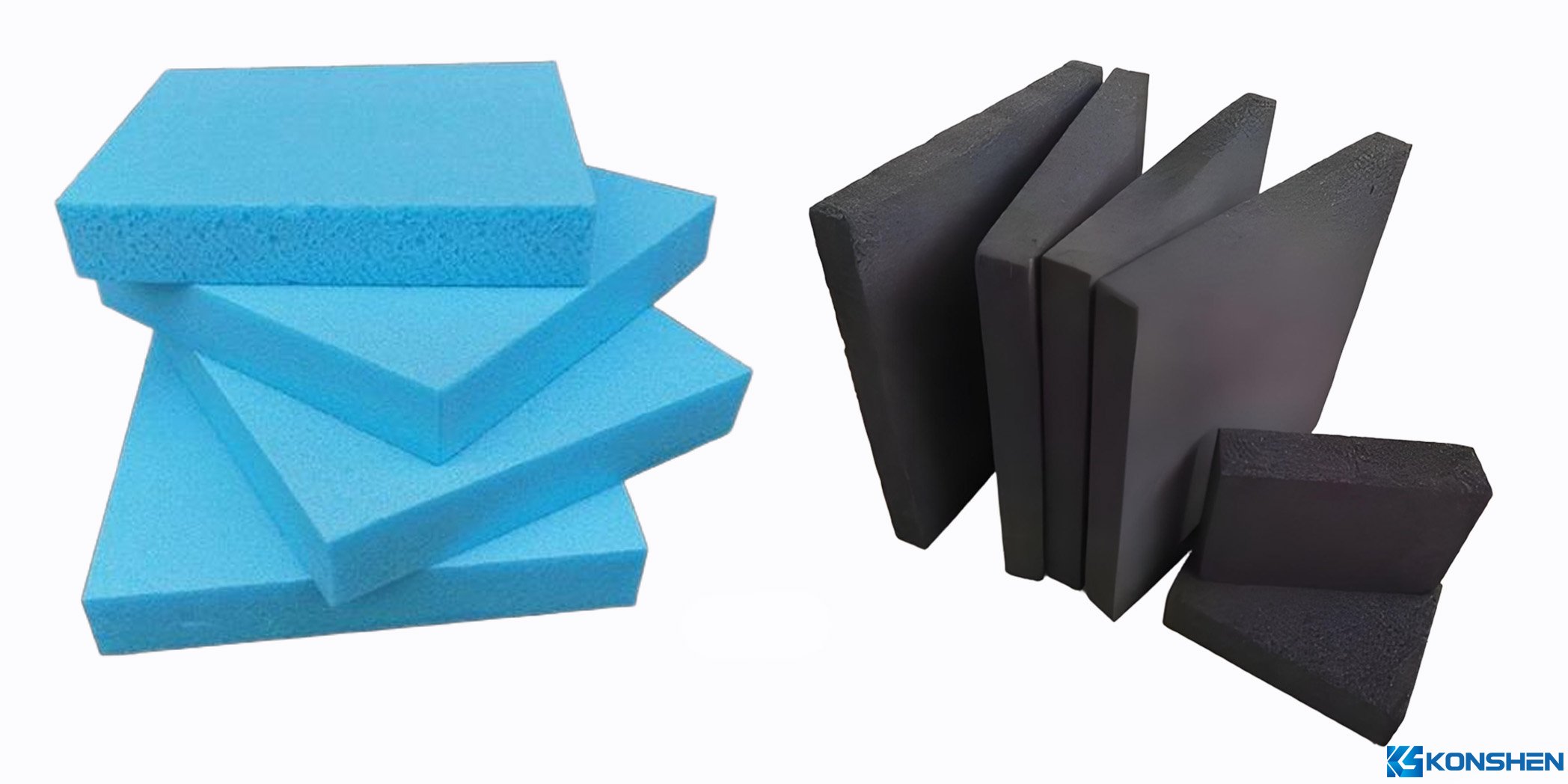

2.6 Foam Boards (EPS/XPS)

2.7 Vacuum Packaging or Shrink-Wrap Packaging

3.Glass Packaging Methods

3.1 Glass Placement Method

3.2 Single-Piece vs. Multi-Piece Packaging Strategies

3.3 Edge and Corner Reinforcement Methods

3.4 Export Transport Packaging Structure Design

3.5 Dust, Moisture, and Anti-Static Packaging Techniques

3.6 Fragile Labels and Tracking Systems

3.7 Transport Weight Limits and Loading Quantity Standards

4. Operational Techniques and Precautions for Glass Packaging and Transport

4.1 Surface Inspection Before Packaging

4.2 Packaging Force Control

4.3 Packaging Safety Tests

4.4 Glass Handling Guidelines

4.5 Responsibility for Damage During Transport

5.Environmental Regulations and International Packaging Compliance

5.1 EU PPWD: Packaging Reduction and Recyclability Requirements

5.2 EU EPR (Extended Producer Responsibility) Mechanism

5.3 Germany VerpackG (Packaging Act): One of the Strictest Packaging Regulations in Europe

5.4 California EPS Restriction: Strict Control on Foam Packaging in the U.S.

5.5 ISPM 15: International Phytosanitary Requirement for Wooden Packaging

5.6 REACH and RoHS: Chemical Compliance of Packaging Materials

5.7 Japan and South Korea: Green Packaging Requirements

In modern manufacturing and global supply chain systems, glass has become a widely used key component in consumer electronics, optical instruments, household appliances, industrial control terminals, and lighting systems. As products trend toward lighter structures and higher precision, the inherent brittleness of glass becomes more pronounced, placing greater demands on packaging and transportation.

In practical logistics operations, glass breakage is often caused by small errors in packaging or transportation. For example, improper placement may create concentrated stress; insufficient cushioning may lead to vibration accumulation; overloaded pallets may cause crate bottoms to collapse; and high humidity during sea freight may weaken paper-based materials due to moisture absorption. These issues frequently arise during transportation but are often discovered only when the customer opens the packages, resulting in batch scrap, returns, claims, or even production line shutdowns—ultimately affecting supply chain stability. Additionally, as countries impose increasingly strict environmental and compliance requirements on packaging materials, glass packaging is no longer merely a cost factor but a system closely tied to quality control, risk management, and regulatory compliance.

This guide provides a systematic overview of the materials, methods, operational details, safety standards, and export compliance requirements involved in glass packaging. Its goal is to help manufacturers and buyers better understand the importance of packaging in the glass industry and how to design safer, more reliable, and more cost-efficient packaging solutions.

Although glass undergoes strict process control before leaving the production line, the real risks begin once it enters logistics. Transportation vibration, loading and unloading impact, stacking pressure, and differences in operator handling all create potential threats that cannot be fully eliminated. Therefore, packaging becomes the most direct and effective protection method. Through structural design and cushioning materials, packaging absorbs impact, disperses pressure, and prevents edge chips, cracks, or surface defects. In many cases, packaging quality determines the final arrival integrity rate.

Damage during transportation creates not only material loss but also additional costs such as re-manufacturing, urgent shipping, warehousing, and manual handling. Industry data shows that reasonable packaging investment significantly stabilizes delivery performance and reduces hidden losses caused by rework and replacements. Good packaging is not merely “protecting the product”—it is a strategic approach to minimizing supply chain risk and ensuring delivery schedules.

Glass is a brittle material and breaks when subjected to impact or point pressure beyond its threshold. This characteristic means it must rely on external cushioning to stay safe. Packaging compensates for these limitations by absorbing the energy glass cannot withstand. In essence, packaging is taking the risk on behalf of the glass.

In export logistics, glass undergoes pallet handling, forklift operations, truck transport, and long-distance shipping by sea or air. Each party in the logistics chain—warehouse staff, drivers, crane operators, and even environmental conditions—can introduce variability. These factors are uncontrollable to the manufacturer. Packaging, however, can be designed, tested, and standardized ahead of time, making it the only fully controllable factor ensuring safe arrival.

A clean, robust packaging structure with standardized materials and clear labeling allows customers to quickly assess a supplier's capability and quality management level. Conversely, inadequate or overly simple packaging creates a perception of high risk and can reduce confidence. Professional packaging enhances customer trust and supports long-term cooperation.

Protective film is one of the most common basic materials used in glass packaging. It is mainly applied to prevent the glass surface from being scratched or contaminated by dust. For export or long-distance transportation, protective film is typically used together with EPE, paper interlayers, and outer sealing film to form a complete protection system. The protective film itself does not provide compression resistance, but it is a key material for ensuring surface quality within the overall packaging structure.

Different types of protective films vary significantly in adhesion, thickness, and temperature resistance, so the appropriate specification must be selected according to the type of glass. For electronic display glass, ultra-clear glass, and products with high light-transmission requirements, the cleanliness of the protective film is especially important. Low-residue films ensure that no adhesive marks remain after removal, preventing any impact on light transmittance or the performance of surface treatments. For glass with AF/AR/AG coatings, the protective film must be made of materials that do not react with or migrate into the coating; otherwise, long-term adhesion may cause localized haze or water marks on the coating surface.

During transportation, the protective film does not provide structural protection—its role is mainly surface protection. Therefore, when developing a packaging solution, the protective film is typically used as the base layer in combination with other cushioning materials.

|

Material Type |

PE Film |

PET Film |

PVC Film |

|

Common Thickness |

30–80 μm |

25–75 μm |

60–120 μm |

|

Adhesion Level |

Low–Medium |

Medium |

Medium–High |

|

Features |

Soft, low cost, excellent conformity |

High flatness, clean, stable, excellent clarity |

Strong flexibility, good scratch resistance |

|

Suitable For |

Soda-lime glass, tempered glass, appliance glass |

Optical glass, coated glass |

Appliance glass panels, large glass parts |

|

Notes |

Poor heat resistance; low-adhesion types may lift |

Higher cost; high-adhesion types not suitable for coatings |

Lower environmental score; high-adhesion may leave residue |

Paper-based materials are among the most fundamental and versatile protective options in glass packaging due to their controllable cost, ease of cutting, and high recyclability. They are mainly used as interlayers between glass pieces to reduce surface friction and prevent minor scratches or contamination during transportation.

Kraft paper has high toughness and is not easily torn, making it the most widely used interleaving paper in the glass industry. White paper is cleaner and produces less dust, making it suitable for optical glass or ultra-clear glass where cleanliness is critical. Interlayer paper with embossed or anti-slip surface treatment is ideal for thin or precision glass, as it effectively disperses localized pressure. Copy paper, with its fine fibers and thin thickness, has been increasingly used in high-precision packaging, especially for coated glass or surfaces sensitive to particulate contamination.

Although paper-based materials are convenient, their hygroscopic nature is an inherent weakness. Under high humidity, paper strength and rigidity decrease. During long marine transportation, paper may curl or wrinkle, causing localized point pressure. Therefore, for ocean shipping, it is necessary to incorporate sealing film, desiccants, or additional external moisture-barrier layers to ensure that the paper maintains stable performance throughout prolonged transport.

|

Type |

Thickness |

Features |

Application |

Advantage |

Limitation |

|

Kraft Paper |

60-120g |

High toughness, tear-resistant, low cost |

Architectural glass, standard ultra-clear glass, tempered glass interlayers |

Durable and cost-effective |

Highly hygroscopic; softens easily in high-humidity environments |

|

White Paper |

60-100g |

Fine pulp fiber, low dust shedding |

High-cleanliness-requirement glass, display glass, optical glass |

Cleaner, reduces paper-dust contamination |

Slightly higher cost than kraft paper; sensitive to humidity |

|

Embossed Paper |

30-60g |

Embossed surface, anti-slip, uniform pressure distribution |

Ultra-thin glass, coated glass, scratch-sensitive glass |

Even pressure distribution, low friction |

Thin material, not suitable for heavy glass |

|

Tissue / Copy Paper |

17-40g |

Very thin, fine fibers, no dust shedding |

Coated glass, optical glass, electronic glass |

Does not damage the surface; high cleanliness |

Poor tear resistance; not suitable for heavy-load glass |

|

Moisture-Resistant Paper |

60-120g |

Moisture-resistant surface coating |

Ocean shipping, high-humidity regions |

Better performance in humid environments |

Higher cost; coating environmental compliance must be confirmed |

|

Kraft linerboard |

150-300g |

Stiff and rigid, used as outer layer or divider |

Pallet base sheets, dividers, structural support |

High strength |

Not suitable for direct contact with glass |

Practical Recommendations (Based on Industry Experience)

Thin glass (0.3–1.1 mm): Embossed interleaving paper or copy paper is recommended to prevent micro-cracks caused by point pressure.

Ultra-clear glass / display glass: White paper is more suitable due to its superior cleanliness.

Export and ocean shipping: Paper materials must be combined with sealing film or desiccants to prevent moisture-induced softening.

Coated glass (AF/AR/AG): Copy paper or embossed interleaving paper is preferred to reduce friction risk.

EPE (expanded polyethylene), commonly known as pearl cotton, is the most widely used single-piece packaging material in the glass industry due to its light weight, softness, and stable cushioning performance. EPE offers excellent compression resilience, meaning it does not easily deform permanently even under prolonged pressure. For glass products with high sensitivity to surface defects—such as tempered glass, ultra-thin glass, and coated glass—EPE effectively reduces point pressure and impact, helping the glass remain stable during packaging.

EPE foam bags provide individual compartments for each piece, making them suitable for assembly-line packaging and improving efficiency. However, EPE is less recyclable than paper-based materials, and in some regions, plastic foam materials face environmental restrictions (e.g., Japan and certain EU countries).

Plywood crates are one of the most reliable outer packaging solutions for exporting large-size glass. Plywood offers consistent structural strength, does not crack easily, and is less prone to deformation, while also being lighter in weight and more cost-efficient overall. Such crates can withstand the concentrated weight of glass and prevent collapse caused by pressure changes during stacking.

The greatest advantage of plywood crates is their high design flexibility. The interior can be customized with supports, dividers, reinforcement strips, and cushioning layers according to the glass dimensions, ensuring the weight is evenly distributed. It is important to note that export crates must comply with ISPM 15 requirements (HT heat treatment or MB fumigation), otherwise customs clearance may be denied in the destination country. In addition, certain EU regions impose maximum weight limits on wooden crates, which requires balancing strength, weight, and material efficiency during crate design.

As a general guideline, when the glass dimensions exceed 15 cm in length or width, plywood crates should be considered as the outer packaging solution.

Honeycomb paperboard is made from multiple layers of paper with a honeycomb-like mechanical structure, offering a high strength-to-weight ratio. It is increasingly common in packaging solutions that prioritize lightweight design, recyclability, and cost efficiency.

For small-size glass (length and width under 15 cm), honeycomb paperboard can be used as pallet panels, interlayers, or even as an alternative to wooden outer packaging. Its vertical compression strength is very high and can withstand stacking pressure, while its horizontal flexibility helps absorb vibrations during transportation. The advantages of honeycomb paperboard include full recyclability, low weight, and low cost. However, it is not suitable for high-humidity environments; prolonged exposure to the moisture conditions typical of ocean shipping may cause the structure to soften. Therefore, for export packaging, it is typically paired with plastic wrapping or a moisture-barrier layer to maintain stability.

EPS and XPS are common rigid foam materials with excellent compressive strength and energy absorption capabilities. They are mainly used as edge supports for glass or as structural fillers inside packaging boxes. Compared with EPE, these materials are harder and can withstand greater load or impact. In wooden crates, foam boards can fill the gaps between the glass and the crate, preventing glass movement during transportation and making them particularly suitable for large-size or multi-stacked glass packaging structures.

However, it is important to note that EPS/XPS materials are restricted in certain regions due to environmental regulations. Therefore, for export packaging, the destination country's regulations should be verified in advance to avoid customs clearance issues.

Vacuum packaging and shrink-wrap packaging are commonly used for precision or high-cleanliness glass products, such as optical glass, antimicrobial glass, coated glass, or industrial glass that requires complete dust isolation.

Vacuum packaging removes air so that the glass fits tightly against the packaging material, reducing movement space and preventing moisture intrusion. Shrink-wrap packaging forms a stable outer layer through heat shrinking, bundling multiple pieces of glass into a single unit that is less likely to shift or come apart during container transport. This type of packaging is more suitable for high-value products or those sensitive to cleanliness and environmental exposure. However, it is more costly and requires specialized equipment.

For standard architectural glass or heavy glass, this method is not recommended, as excessive tightness may increase the risk of point pressure. Therefore, vacuum or shrink-wrap packaging is considered a supplementary solution for specific scenarios rather than a universal packaging method.

The key to glass packaging lies not only in material selection but also in whether the method is appropriate for the glass’s size, weight, thickness, transportation distance, and mode of transport. The level of professionalism in packaging directly determines the final breakage rate, delivery stability, and the customer’s overall evaluation of the supply chain.

Flat Placement or Vertical Placement? The Real Differences from Industry Experience

Whether glass should be placed vertically or laid flat is one of the most frequently discussed topics in the industry.

In theory, flat placement distributes stress evenly across the entire surface, as the whole plane bears the load. However, during real transportation, flat placement is more likely to cause “resonance” between the glass and cushioning materials due to vehicle vibration, resulting in micro-cracks—especially for thin glass.

On the other hand, when glass is placed vertically, gravity is concentrated on the lower edge. Although edges are the most fragile part, the risk can be well controlled as long as proper edge cushioning materials are used. For this reason, most exporters prefer vertical placement for medium- to large-size glass.

For smaller pieces or thick glass, the risks of flat placement are manageable, especially when quantities are small and transportation distance is short. Conversely, for long-distance ocean shipping, truck transportation, or routes with significant container vibration, vertical placement reduces point pressure and impact, making it suitable in most situations.

A-Frame and L-Frame: Practical Usage Standards

A-frames and L-frames are commonly used for bulk transportation of large-size glass.

A-frames have a symmetrical structure suitable for double-sided loading.

L-frames are mainly used for single-side loading.

A crucial requirement is that the bottom of the glass must be cushioned with soft materials so that weight does not act directly on the edge. The frame angle is typically 5–9°, ensuring that the glass remains in contact with the support surface without slipping due to excessive tilt.

The load-bearing beams at the base of the rack must be strong enough. Many breakage incidents do not originate from the transportation process, but from insufficient welding or load-bearing design of the frame itself. If the base is not reinforced, uneven load distribution can cause sudden vibration during handling and break the glass. Therefore, choosing A-frames that meet export standards is more effective than selecting thicker glass or adding more cushioning.

Placement Differences Between Film-Coated Glass and Bare Glass

Glass with protective film tends to create an adhesion effect. When multiple pieces are tightly stacked, the friction coefficient increases, and transportation vibration can generate shear force between the pieces. Therefore, film-coated glass requires additional interlayers during stacking or vertical placement to reduce adhesion risk.

Bare glass, on the other hand, is more prone to scratching and must have separation material between every piece. Even minor vibration can create visible surface scratches if glass surfaces rub directly against each other.

Glass Size and Thickness Determine Stacking Quantity

The size and thickness of glass largely dictate how many pieces can be safely stacked. Small-size glass has concentrated weight and a small contact area, so stacking risk is much lower than for large glass. For example, 50 mm × 50 mm glass can be stacked in dozens of pieces safely. However, when the size increases to 300 mm × 300 mm, even with a thickness of 5 mm, excessive stacking can overburden the bottom layers, potentially causing micro-cracks during long-distance transport.

For ultra-thin glass (0.3–1.1 mm), nearly all factories adopt a single-piece interlayer approach, because even minor point pressure can cause irreversible damage. The main risk for thin glass during transportation comes from pressure marks rather than impact, making interlayer material and tension control more critical than stacking quantity.

How Interlayer Materials Affect Transport Stability

Interlayer materials help distribute pressure, allowing the glass weight to be transmitted evenly. If the interlayer is too soft, the glass can "sink" into it, creating point pressure. If the material is too hard, stress becomes concentrated in localized areas, which is equally hazardous.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Combinations

Single piece + interlayer: Highest safety, highest cost; suitable for high-value glass.

Multiple pieces + paper interlayer: Low cost, high efficiency; not suitable for long-distance ocean shipping.

Multiple pieces + EPE: The most common structure, balancing cost and safety.

Multiple pieces + EVA/PP: Professional-grade solution, suitable for industrial glass requiring very low breakage rates.

When selecting a packaging solution, companies should consider total cost, including breakage cost, replacement cost, transportation method, and customer risk tolerance, rather than focusing solely on packaging material cost.

Why Edges Are the Most Fragile Part of Glass

Glass compressive strength is much higher than its impact strength, and edges are where stress is most easily concentrated. Even minor chips can significantly reduce impact resistance, which is why over 70% of transport damage occurs at the edges. During long-distance transportation, glass edges are constantly subjected to vibration, point pressure, friction, and weight transmission; failure to properly manage any of these factors can trigger crack propagation.

Common Reinforcement Methods and Industry Experience

Tempered glass, though strong, is still vulnerable to point impacts, especially at corners. Reinforcement must cover the corners and ensure the material remains stable. Ultra-thin glass requires full-surface support to prevent edge overhang and bending; therefore, reinforcement must protect edges while maintaining overall structural stability.

Common edge reinforcement materials include U-shaped foam, rubber strips, thick EPE, and paper corner protectors. The key is not the material itself, but its fit and stability. If corner protectors slip during transport or are not thick enough to truly suspend the glass, the reinforcement loses effectiveness.

In practice, packaging leaves at least 20–30 mm of cushioning space between the glass edges and the box, and the material must have sufficient resilience to absorb energy during sudden impacts.

Internal Cushioning Structures

Wooden crates typically include several key internal structures: peripheral supports, bottom shock-absorbing pads, lateral fixing blocks, and top pressing boards. Together, these elements keep the glass stable and immobile within the crate. Cushioning structures must balance energy absorption and support—materials that are too soft or too hard can both introduce risks.

Container Loading and Securing Methods

One of the most critical steps in export transport is proper container loading. From the factory to the destination port, truck vibrations are often more severe than the ocean voyage itself. Therefore, wooden crates or A-frames must be secured inside the container using straps, stretch film, and wooden wedges to prevent movement during turns, braking, or jolts. Many breakage incidents result from inadequate securing rather than poor crate design.

Importance of Bottom Load-Bearing Design

If the bottom of a wooden crate is not properly designed to bear weight, long-distance transport may cause central sagging, leading to uneven pressure on the glass. During crate construction, factories typically reinforce the crate bottom with a central load-bearing beam or use a pallet frame to ensure the structure remains stable under long-term loads.

Humidity Risks in Ocean Transport

Humidity inside shipping containers often exceeds 80%, and temperature fluctuations can create container rain. If glass is not protected with plastic wrapping or if desiccants are not added, paper interlayers or wooden crates may absorb moisture and soften, leading to edge pressure changes or even mold. Additionally, if termite eggs remain in the wooden panels of crates, long-term high humidity and temperature can hatch termites, contaminating the glass.

The standard practice for export glass is therefore: single-piece plastic-wrapped glass + desiccant.

Too many desiccants waste cost, while too few fail to protect the glass adequately. Desiccant quantities are usually based on the container volume and are placed at multiple locations inside the box to ensure uniform moisture absorption.

Anti-Static Requirements for Specialized Industries

Glass used in electronics, semiconductors, and touch devices is highly sensitive to static electricity. Static can attract dust, affecting adhesion and cleanliness; some coated glass may even suffer coating damage due to electrostatic discharge. These industries typically require anti-static bags, anti-static foam, or anti-static sprays to maintain a stable packaging environment.

Labels such as “FRAGILE” or “HANDLE WITH CARE” effectively alert handlers to take care. Studies show that properly labeled cargo is less likely to experience rough handling.

Labels must be placed in visible locations and correspond to the transport method. For vertically placed glass, arrows indicating “this side up” are necessary; for A-frames, labels should indicate removable points and lifting positions.

For high-value glass or supply chains requiring liability tracking, vibration recorders and tilt indicators are increasingly used. These devices show whether the cargo experienced severe impact or tilting during transit, helping determine responsibility and encouraging proper handling.

Why Weight Limits Are Critical for Glass

Glass has high density and concentrated weight, making crates prone to overloading. Overweight crates can cause:

Difficulty in manual handling

Deformation of pallet bottoms

Increased tipping risk with forklifts

Exceeding ocean transport limits

Many countries regulate maximum single-pallet weight, especially in the EU where labor safety rules are strict. A general guideline for a single wooden crate is 1 ton maximum.

Size Variation Leads to Large Differences in Loading Quantity

For example, 2 mm thick glass may seem light, but if the size is large and the crate is fully loaded, the total weight can exceed safe handling limits. Therefore, factories usually set a maximum number of pieces per crate based on size and weight, rather than simply calculating by thickness or weight.

Low Piece Count + High Cushioning Strategy for Large Glass

For glass exceeding 1 meter in dimension, transport risks rise sharply. Many export factories adopt a “low piece count + high cushioning” approach: reduce stacked pieces and increase cushioning and support structures to ensure overall stability.

Avoiding Bottom Pressure Damage Through Multiple Boxes

Heavy, thick glass placed in a single large crate can deform at the bottom due to prolonged pressure. Splitting into multiple smaller boxes not only distributes weight but also enhances transport safety—a practice increasingly recognized as standard in the industry.

Before starting packaging, a systematic surface inspection is essential. The inspection should follow an established process:

Confirm that the surface is free from obvious scratches, oil stains, or dust.

Check the edges for chipping.

Inspect coated areas for color variations or spot defects.

For high-precision or high-value glass, inspections should be performed in a cleanroom, using lint-free gloves and specialized lighting (yellow light, three-light, or blue light) to detect minor scratches or imperfections. Any issues found should be documented and isolated with the quality department to prevent defective products from entering the packaging process.

Maintaining pre-shipment records (photos, signed inspection reports) not only improves internal traceability but also provides critical evidence in case of disputes.

This is particularly important for ultra-thin glass. Many damages are not caused by strong external impacts but by over-tight bundling or excessive fixation inside the crate, leading to localized high pressure and hidden cracks.

Guidelines:

Stable but not pressurized: Fixings and corner protectors should prevent glass from sliding but should not directly press on the edges or surfaces.

Use cushioning materials with good rebound to maintain a small gap that absorbs vibrations and avoids point pressure.

For straps and stretch films, tension should be controlled with a tension gauge, and standard operating parameters should be set at workstations to prevent over-tightening due to individual habits.

Transport testing is a key step to verify the reliability of packaging solutions. Common methods include stacking tests, drop tests, and vibration tests.

Stacking Test

Purpose: Apply a static load equivalent to multiple stacked layers and observe whether the box or internal materials deform permanently or fail.

Load Calculation:

Calculate the pressure the bottom layer may endure based on actual transport or storage. For example, if stacking 2–3 meters high with 4–6 boxes on top, apply a static load equal to the total weight above. If requested by the customer, use a safety factor of 1.5–2.0.

Load Application:

Place the package on a flat surface and apply weight using a static load press, weights, or loading plate. Ensure the load is evenly distributed to avoid localized deformation.

Duration:

Standard is 24 hours, referring to ISTA 3A or transport packaging norms. For medium-sized factories, a 12-hour quick verification may be used initially, but the 24-hour standard is recommended before mass production.

Observations:

Before and after loading, check

Cardboard for permanent dents, bulging, or bottom deformation

Internal foam or paper supports for deformation causing glass displacement

Glass for hidden cracks, edge chipping, white spots under pressure, or stress concentration

Acceptance Criteria:

Minor surface impressions are acceptable, but there should be no structural collapse, glass displacement, breakage, edge chipping, or severe permanent deformation of internal cushioning.

Drop Test

Purpose: Verify whether glass cracks, chips, or shifts during sudden impacts in handling.

Drop Height: Usually based on product weight and transport method, e.g., 1 m for typical handling drops; heavier packages may use 60–80 cm.

Drop Directions: Sequential drops on 6 faces, 8 corners, 12 edges, with focus on corners and long edges due to concentrated stress.

Standards: Reference ISTA 1A/2A or customer requirements; record glass displacement, breakage, silk-screen peeling, and packaging deformation.

Acceptance: Minor surface dents are allowed; no breakage, scratches, or displacement.

Vibration Test

Purpose: Simulate continuous micro-vibration and resonance during transport to detect potential hidden issues like friction wear, cracks, or loosening.

Parameters: Use a mechanical vibration table (common in factories), vertical vibration, 3–5 Hz to simulate truck/container movement.

Test Method: Fixed frequency or sweep frequency (e.g., 3–7 Hz back and forth) for 30–60 minutes.

Observations: Check for friction marks, loosening, minor edge chipping, cracks, or support fatigue.

Acceptance: Glass should remain intact, packaging should not show structural damage; if wear is observed, increase foam thickness, add fixing points, or optimize design.

For high-value or large-volume shipments, at least one complete test per packaging type should be performed and recorded. Basic testing can be done using simple load devices, vibration tables, and height measurement tools, avoiding high post-shipment rework costs.

Handling is a high-risk step for breakage. Proper operation greatly reduces accidents:

Prefer mechanical equipment (suction cups, forklifts with padding, anti-scratch lifting straps).

Ensure operators are trained and authorized.

Large single pieces require at least two operators, moving synchronously to avoid stress concentration.

Maintain cushioning between glass and surrounding structures; avoid direct contact with hard surfaces.

For manual handling, clearly define travel routes, temporary supports, and assign personnel to guide operations.

After handling, re-check packaging stability to ensure no loosening or displacement occurred.

Damage during transport is often the core of disputes. To minimize disputes and clarify responsibility:

Document the entire packing process with video and photos; record crate numbers, labels, and strapping methods.

Use vibration recorders or tilt indicators for key batches to provide data for liability assessment.

Contracts should clearly define packaging standards, transport methods, and responsibilities, including claim procedures and deadlines.

In case of damage, immediately photograph and preserve the site, then file a claim with the carrier. Use records to determine whether the issue was due to packaging design/execution, and decide whether to address the problem with the transporter or internally.

For glass products exported to regions such as the EU, the US, Japan, and South Korea, the choice of packaging materials, weight limits, recyclability, and chemical composition can all affect whether the product can successfully clear customs and reach the customer.

The European Union Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive (PPWD) is a fundamental regulation that all companies exporting to the EU must comply with. Its core objectives include:

Reducing unnecessary packaging weight and volume

Packaging should not use excessive materials just to appear “more robust.” Materials such as plywood, EPE, and foam must be reasonably designed according to product characteristics, avoiding over-cushioning or multiple redundant layers. Overly heavy packaging may be deemed “unreasonable packaging” and, in some countries, could incur additional recycling fees.

Ensuring packaging materials are recyclable or reusable

The EU favors materials such as paper, wood, and recyclable plastics, while increasingly restricting non-recyclable single-use foams (e.g., some EPS types). For high-value glass products, such as electronic display glass or ultra-thin glass, it is recommended to use EPE, EVA, or PP recyclable materials instead of traditional foam to reduce the recycling burden in the destination country.

Materials must comply with heavy metal and hazardous substance limits.

Total content of lead, cadmium, mercury, and hexavalent chromium in packaging must be below 100 ppm. For glass products serving the electronics industry, packaging materials must also avoid certain persistent toxic additives.

Country-specific implementation

PPWD enforcement varies by country. Germany, France, and Italy, for example, have stricter packaging declaration requirements, and some countries require importers to provide an annual recycling plan for packaging materials. For exporters, providing a packaging BOM (Bill of Materials) in advance to clients can significantly reduce customs clearance obstacles.

In recent years, EU member states have strengthened the EPR (Extended Producer Responsibility) system, requiring that “whoever produces, is responsible for the post-consumer recycling and disposal of the product.” For exporters, the main impacts include:

Packaging must be registered with an EPR number in the destination country

Many e-commerce platforms (e.g., Amazon EU) now require all products to provide EPR registration proof. Even items such as glass cover panels, glass handicrafts, or panel accessories with individual packaging fall under the EPR scope.

Importers must pay packaging recycling fees

The more difficult the packaging material is to recycle and the larger the quantity, the higher the fees the importer must bear. As a result, many European customers request suppliers to adopt recyclable packaging solutions at the ordering stage to reduce future EPR costs.

Non-compliance may lead to product delisting or customs delays

For foreign trade companies, this often translates to customers requesting:

Packaging material list and weight

Material recycling category (e.g., “PP 5,” “PAP 20”)

Confirmation that used plastics comply with REACH restrictions

Preparing these data in advance can significantly improve trade smoothness and reduce clearance risks.

Germany's VerpackG is considered one of the most strictly enforced packaging regulations in Europe. The main requirements include:

All packaging must be registered on the LUCID Packaging Register

Whether exporting glass cover panels, glass window panes, or glass samples, any packaging entering the German market must be pre-registered.

Importers must participate in the Dual System and pay recycling fees

Fees are calculated based on packaging material and weight. Therefore, German customers often request suppliers to minimize the proportion of plastics, and prioritize recyclable materials such as paper and wood.

Packaging must indicate recyclability symbols and material classification

For example:

Cartons: PAP 20

PP bags: PP 5

EPE: PE 4

Failure to mark correctly is considered non-compliant.

Advice for glass exporters:

Coordinate packaging structures with the customer in advance, avoiding materials highly restricted in Germany, such as non-recyclable composites or excessive EPS usage.

The United States does not have a unified federal regulation for packaging; instead, state-level regulations apply. California imposes the strictest restrictions on EPS (expanded polystyrene foam). Impacts include:

Although EPS is still occasionally used as lining in wooden crates for glass, for electronic glass, display glass, or optical glass, it is advisable to avoid EPS to prevent restrictions on local sales.

All wooden crates and pallets made of untreated solid wood must comply with ISPM 15 (International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures No. 15), otherwise they cannot enter most countries. Key requirements:

Wood must be heat-treated (HT) or fumigated (MB).

Crates must display the IPPC mark and HT/MB number in a visible location.

Composite wood panels (plywood, OSB, MDF) are exempt from this regulation.

For glass exports, most crates are plywood-based, which naturally comply. However, if using solid wood A-frames, reinforcement beams, or pallets, ensure the wood is treated and properly marked.

Although REACH and RoHS are often associated with electronics, they also apply to packaging materials, especially:

Plastic bags

Foam materials (EPE, EVA, PE, PU)

Shrink film, vacuum film

Anti-explosion film

Main requirements:

Packaging must not contain REACH restricted SVHC (Substances of Very High Concern).

RoHS restricts 10 hazardous substances, including:

Lead, cadmium, mercury, hexavalent chromium

Phthalates and other plasticizers

Non-compliant materials may prevent use in the electronics industry. For electronic glass, touch panels, and cover glass, use packaging materials already tested for REACH/RoHS compliance and keep supplier documentation for verification.

Asian markets also impose strict requirements on packaging materials:

Japan:

Limits the use of foam packaging; encourages paper and wood materials

E-commerce platforms require packaging to be easy to disassemble and recycle

Extra fees on plastic waste

South Korea:

Plastic packaging must be recyclable

E-commerce orders must indicate packaging grade, e.g. recyclable or hard-to-recycle

For glass exporters to Japan and South Korea, reducing plastic use and adopting paper honeycomb boards and eco-friendly EPE is becoming a necessary trend.

Glass packaging is not only crucial for transport safety but also impacts cost control and international compliance. With increasing product sizes, thinner glass, and diverse applications, packaging has become a key factor in ensuring delivery quality. Selecting appropriate materials, scientifically designing packaging structures, and standardizing operational procedures can significantly reduce breakage rates, prevent returns or delays, and minimize customer disputes.

At the same time, as global environmental regulations become stricter, companies must consider lightweight, recyclable, and legally compliant packaging. A systematic and standardized packaging solution is essential for enhancing competitiveness and ensuring stable supply in the glass industry.

Ready to take your glass project to the next level? Contact us today to discuss your custom glass needs and get a quote!

contact us